|

Before 1968...before 1919....DC witnessed a race riot, its first-- one that engaged several period writers or literary figures. When was it, and what happened?

0 Comments

As this fascinating graph at peakbagger.com illustrates, Washington begins as a relatively big American city—a crowd of clerks come down from Philadelphia. During the expansionist and war-ridden 19th Century, the period when the capital mattered the most to the fate of the country, it fell into relative burgdom as the demographic center of the U.S. shifted away from the East Coast. In the 20th Century came air conditioning, a depression and government expansion, and two World Wars and a Cold War. From 1970 to 2018, according to Census data, the capital’s population grew by over 130%, a rate more like that of Dallas or Miami than that of the Northeastern cities. Washington, until just the other day a hamlet where (Gore Vidal) "everybody knew everybody," has, rather suddenly, become just big enough to be unknowable, and therefore unknown. All the more so because so many of the people who do so much of the talking and writing about and on behalf of it have moved from elsewhere. Although the city no one loves and no one quite knows has been written about, to date the work has been done piecemeal, a hundred Mister Magoo's views of the elephant. Odd, that a city that touches the lives of so many people all over the world—a city of analysts and reporters, no less—should have so little idea of itself, and so few epics to go to begin to get one. All else being equal, the more people a town has, the more readers and writers, the more writer's groups and centers and conferences, the more (for now) book-buyers and libraries and bookstores, and the bigger the so-called literary community. For now, though, none of this growth has yielded much in the way of those big books. Perhaps this is because our most ambitious storytellers, in realism and otherwise, now tend to go into the movies and (lately) TV—where we can find complex pictures of Baltimore, but, as yet, nothing more than the usual Cardboard Capital. Interested in official poets? You may need a map. In the United States alone, notably since the 1990s, there’s a great national forest of them. The Librarian of Congress nominates the best-known one, the Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress. But forty-five U.S. states also have them; most of these positions are relatively new. So do the District of Columbia (though the seat is currently empty) and, since 1981, the Overseas Territory of Guam. Many of the 2,000-plus American counties have them. Cities and towns have them. Foundations have them. Churches have them. National Parks have them. The list doesn’t end there.

According to the NEA-Census Survey of Public Participation in the Arts, as of 2017 about one in eight Americans read any poetry that year, counting works published online. Granted that the figure doesn’t count attendance at readings or slams or other performances, live or on YouTube or otherwise, it's still far below the rate for movies (58.6%) or prose fiction (41.8%). But our national, state, county, and municipal governments haven’t, as yet, anointed thousands of official filmmakers or novelists. Even Hollywood is a lot older than the position of U.S. Poet Laureate. So why poets? Official poets generally serve short terms, and perhaps significantly, are paid little or nothing. In exchange for what amounts to an unheard-of (for most poets) form of publicity, they are expected to perform certain public and generally teacherly and often activist duties. Is there a quid pro quo? The Academy of American Poets, “the nation's largest membership-based nonprofit organization advocating for American poets and poetry,” even publishes what amounts to a set of guidelines for those jurisdictions and organizations still looking to acquire an official bard or bards. (The most interesting takeaway: a state official poet, on average, is worth four city poets.) The DMV has (or in the case of the national Laureate, oversees) its own share of offices. Here are the ones I was able to track down. The newest are listed first: Estab. / Patron -- Current Poet (term) 2018 Prince George’s County -- J. Joy “Sistah Joy” Matthews Alford* (2018-) 2014 Prince William County -- Natalie Potell (2018-) 2005 Takoma Park, MD -- Kathleen O’Toole (2018-) 1998 Montgomery County -- Cathleen Cohen (2019-) 1984 District of Columbia -- (vacant since the death of Dolores Kendrick in 2017) 1979 Alexandria, VA -- KaNikki Jakarta (2019-) 1959 Maryland -- Grace Cavalieri (2018-) 1937 United States -- Joy Harjo (2019-) 1936 Virginia -- Henry Hart (2018-) *According to her web site, retrieved 24 July 2019, Ms. Matthews Alford is also, since 2016, the Poet Laureate of Ebenezer AME Church in Fort Washington, MD. Arlington, Virginia? It had a poet between 2016 and 2018, when the office was eliminated. Katherine E. Young was its first and, to date, only Poet Laureate. However, the position will soon be restored. What should we do with Democracy, that love triangle set in the Gilded-Age capital? We should read it. When we do, though, we run into two problems the original readers didn't. First, reputation. Hey, wait—there is a Great Washington Novel! Our expectations are likely to be too high. Second, the big title seems to promise a panoramic extravaganza. You know: Senator Claudius takes the wrong exit and runs his German horse over a gravedigger...and dozens of people who in normal life barely cross paths are…haplessly entangled in as many subplots…that…illuminate every social nook of every social cranny, etc. The book's not like that. It's a sardonic snow globe. Inside are a white dome, a handful of cozy or official interiors, some Virginia greenery, and a dozen-odd legislators, appointees, diplomats, lobbyists, and hangers-on. There's a farmer President who's in over his head, but he figures only peripherally, and the story largely stays away from the Capitol, and also from the newspapers. There are no civil servants, no back alleys, no Chinatown, no police, no morphine addicts, and no horse dung. The Civil War ended, there are some ruined Confederates, but there’s no sign of Reconstruction or of its failure. "Negroes" figure only as wallpaper. Indeed, the book spends more time with the wallpaper in the heroine's rented house than it does with all its freedmen and maids put together. The heroine, Mrs. Lee, is a demographic compromise. A relation of the Great Virginian, Robert E., she's also a New Yorker and (as widow) heir to a business fortune. Bored with New York, with Europe, and with hard books, in that order, she moves with her younger sister to Lafayette Square (Henry Adams lived there) to play political tourist. (It's Lafayette Square before the tour bus; it’s always empty.) Half-blind to her own motives, she gets mixed up with and taken in by a forceful, fortune-hunting sophist from Illinois, Senator Ratcliffe, who stands in for the Grant-Hayes era’s politics generally. The third side of the triangle is a shabby Virginian knight—shabby in the book’s terms—who sees through and, with the sister’s help, tries to steer Mrs. Lee away from Ratcliffe, who’s also dying to be President. (Mrs. Lee has badly underestimated the rat, mainly because he doesn’t speak French.) The story gets underway quickly, has few flat spots, and doesn't linger at the end. It isn't overfilled with officials, either. Adams has chosen his focal characters carefully. A sequence of leisurely set-pieces provides an excuse for giving close readings of them and of their exchanges. There's Mrs. Lee's parlor; riding in rural Arlington; a steamer trip to Mount Vernon; a blowout at the British embassy. There's plenty of nastiness or gamesmanship, depending on your point of view, but no weapon heavier than a cane is drawn. This is an action story—a great deal happens—in which the talk is the action. There's a third voice in the dialogues, too: Adams' narrator, who pretends not to know everything about his characters, also maintains a running commentary on them; it’s like those reflective asides that break up medieval treatises. Much of it treats the differences between how they see themselves and how others see them, and how the truth of them lies somewhere in between, though neither they nor the narrator attempt to say exactly where.

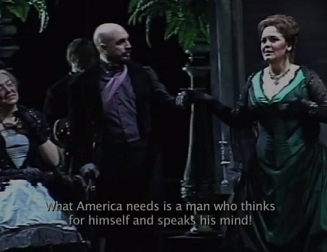

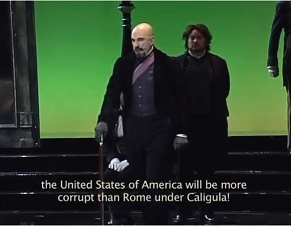

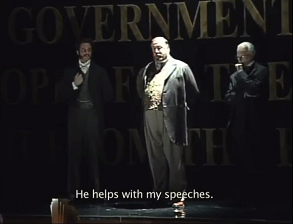

The book, published anonymously in 1880, is a refresher for those of us who’ve forgotten that unfit executives and amoral legislators weren’t invented yesterday or even in our lifetimes. Through Ratcliffe’s speechifying, Adams even attempts to explain why it’s like that and perhaps, as country and prizes grow ever bigger, cannot help but be like that. Indeed, Democracy feels like Adams’ shot at answering this: “From John and John Quincy to this…how did things go so wrong?” What could be more useful reading than that? PHOTOS - CREDIT: Scott Wheeler (YouTube Channel). Stills from "Democracy: A Sampler," from 2005 Washington National Opera production of Democracy, An American Comedy (2002) by Scott Wheeler (music) and Romulus Linney (libretto). Retrieved 11 July 2019. Ever wanted to know what books are set in the District? The crowdsourced project DC By the Book has a map of scenes from fiction set within the District. Search for a book or books, click on the location on the map, and you get an excerpt.

For example, here's the text from one of the 21 locations from David Swinson's 2011 police-detective retrospective, A Detailed Man: "So I walk 5th Street to H and head west through Chinatown...I feel like this neighborhood – afflicted with dilapidated, vacant row homes and thriving Asian-owned liquor stores. The streets are dark for lack of working lamps. But the liquor stores shine through like beacons." The project also includes collections of short stories, like Edward P. Jones' All Aunt Hagar's Children. From the web site: "DC By the Book is the brainchild of Tony Ross and Kim Zablud of DC Public Library. The project explores the richness of non-Federal civic life in Washington and its character as a city, as brought to life by fiction. The project goal is to highlight and crowd-source passages from the (largely undiscovered) rich body of literature set in DC that illuminate its social and geographic history." This sculpture is the so-called Adams Memorial. It’s located in Rock Creek Cemetery—which, incidentally, is not in Rock Creek Park but in Fort Totten. Henry Adams commissioned it after his wife’s suicide in 1885; he was later buried there himself.

According to local historian James Goode’s 2008 survey, Washington Sculpture, the memorial, by Adams’ friend Saint-Gaudens, was erected in 1890-91, and restored, by the Adams family, in 2002. Deliberately androgynous, derived partly from the sculptor’s study of Buddhas, it bears no inscriptions. Goode writes: “The sculptor called it The Mystery of the Hereafter, while Adams called it The Peace of God that Passeth Understanding…Mark Twain’s remark that the figure embodied all of human grief led to its most commonly but incorrectly used name of Grief.” The subject of this month’s upcoming Capsule: Henry Adams’ Democracy (1880). |

AuthorI'm a freelance writer and editor who lives in Washington, D.C. Archives

March 2020

Categories |

© 2016-2019 Nathaniel Koch Email: [email protected]

RSS Feed

RSS Feed