|

Which prolific Washington-born and based writer was, according to some sources, the most widely read American novelist of the late 19th Century?

1 Comment

It walks! It talks! It’s alive! Here’s one panel from Gore Vidal’s long picture, and he wasn’t far from a lot of the subjects, of what lies under the marble and the reliefs and the dead writing of the political histories. That is, unapotheosized hairy human beings, drinking and lying and bribing and cheating and crashing cars and showing off and getting over and generally behaving badly. They say history is little more than the record of men’s crimes, but that’s only a fancy thought. Crimes need people to commit them; here they are.

It's the story of two families—call them Money and Power. Money is headed by Blaise Sanford, a Washington newspaper ogre from the pre-TV era, Power by a smooth but diffident Western Senator (Burden Day) and his handsome young assistant and protégé, Clay. (The Senator treats his assistant so much like a son that he might as well be one.) The families get entangled near the start of the book by the elopement of the publisher’s daughter, a monster princess named Enid, for whom Clay has spurned the Senator’s own daughter, Diana, who later takes up with Blaise’s shy, snack-loving son, Peter. Around them swirl a dozen or so major characters—rich dowagers, corrupt oilmen, ambitious journalists. All rub elbows with real presidents and kings and magnates, who are entertainingly belittled (literally so in the case of the diminutive George VI) in Vidal’s now-here-they-are-naked manner. But the book’s also basically a political version of Joseph Manckiewicz’s All About Eve (1950), with the amoral understudy from the provinces stealing the footlights from the flawed but more principled aging star—and roping in a bandwagon of writers and producers along the way. This study of what ambition does to you, and via the national control room to us all, is an ensemble, but when we’re let in on someone’s thoughts they're usually the Senator’s or Peter’s. True to its title, the entire story is set in the capital, from the late 1930s through the Korean War, FDR through Eisenhower—mid-century modern Washington. Unobtrusively, we are shown how the coming of psychiatry, television, scientific polling, and similar novelties affected politics and life, and also how FDR’s war (as Vidal sees it) changed the formerly small Southern capital: a faster pace, more brighter and ruder people, ever more and more brighter and ruder people. Though it’s a panorama, at least of what used to be called White Washington, it’s a compressed one. The scene’s the cloakroom, the country club, the big house, except when characters downsize to quarters like then-“Negro” Georgetown. Everyone who isn’t powerful or rich or on the way to being so is even more marginal here than Henry Adams’ Negroes and maids; whatever it is these thinking parts think and do all day, the writer isn’t about to tell us. This is partly by way of the book’s putting over the point of view of its characters. But it’s also because in Vidal’s metaphysics such people don’t really exist: what exists is only whatever, for a mayfly’s moment, moves the world’s needle. That Washington, D.C. is entertaining yet cramped, and spirited yet joyless, has something to do with this. But it’s also got to do with the writer’s relationship with his characters. They seem to have been created, in all the teeth and claws which at times seem to be all they are, merely to be first tempted and then made ridiculous by their creator, who runs them through their paces like a martinet's corps de ballet. Although there’s plenty of I-want-this and consequent dramatic interest—and the book is never boring—the characters are rarely allowed to breathe, let alone surprise the all-knowing narrator, who (especially in the dialogues) is always two steps ahead of them with his color commentary. Much of it is devoted to anatomizing the various grades of subtlety in insult. No writer takes more care or delight in setting up and then examining slight, cruelty, and contempt—and Vidal, who was stuck with the short end of a thousand pre-Rainbow Flag slights, is good at it. The first problem with this highly entertaining book, then, has to do with world-picture. The few people in it who think at all, and a lot of the ones who don’t, are nihilists, living for the scratching of itches, for the applause and the trophies, for the sand castle and the wind—for what the Authorized Version calls vanity and philosophy used to call divertissements. What we get, in short, is Vidal's own neo-paganism diffused through the cast, who in places talk like a group of schoolkids who’ve just stumbled onto the Wisdom Books: the lordship of futility is not argued, merely bracingly insisted upon. Technically, the trouble is that this choice allows for only a limited and tedious lot of motives. Everyone’s doing it all for nothing, even if some of them don't know it yet. As Peter tells himself in the summing-up: The generations of man come and go and are in eternity no more than bacteria upon a luminous slide, and the fall of a republic or the rise of an empire…are not detectable upon the slide even were there an interested eye to behold [it]… So the book ringeth throughout. But granted that it's more satirical than realistic, this is at best wildly inaccurate: at no time has nihilism been commonplace in New World heads, not even during the mid-century heyday (which it details) of materialism and positivism, Marx and Freud. This isn’t Washington then or now; it’s a vision of Washington as if it were Ancient Rome under Emperor Democritus. The book’s second fault is not the writer's but was, as it were, thrust upon him. Unlike the author himself, the Washington People in the book are, nearly to a man and woman, philistines. At one point Vidal’s mutable poet-critic, one of the exceptions, complains about it himself. Nuts and bolts, deeds and parcels, who’s up who’s down: that's the business of the federal republic, just as it is of the fifty farm leagues where (as Vidal painstakingly depicts) the rehearsals for the Show begin. The general local practical-mindedness makes for an accurate social picture, but it doesn’t always make for the most absorbing one. Back to the good stuff. The book’s easy to read: the plain writing is faultless, even flawless. The language isn’t showy (I admit I had to look up valetudinarian). Vidal likes to use run-on for satiric or ironic effect, and he likes to save the stinger for the tail. The plot is solidly built: no scene is too long and no one drifts offstage for too long or for no reason. If the characters’ inner lives are a bit sparely furnished, well, this is a very big 400-page book, and the emphasis is on the externals, on what people wear and eat and sit on and say and what they really mean when they say it. Years pass; people flip and flop, come and go; wives and houses and magazines and ideologies trade hands. Vidal stage-manages all this whirl brilliantly; there's no trouble remembering who's who. And he doesn't overdo the period furniture. No rumba. No baseball. There's one period car, and one or two hats on men, one of them in a movie in-joke. Period politicians, period films, and period slang, along with just-arrived ideas and technologies, carry much of the weight of the chronological scenic design. (This minimalism cuts both ways. On the one hand, the book’s departed scene feels fresh, like the present; on the other, it feels fresh, like the present.) Though it’s not a satire per se, everyone is a little cleverer and worse than he is or would be in life, and so all the dull bits are left out. Washington may be a prosaic town, but it's also home to the "the nation's oldest poetry journal," as it calls itself. One hundred thirty years: that's how long Poet Lore has been in business. The biannual, which has published (among others) Rilke, Mallarmé, and Verlaine, is published by the Writer's Center of Bethesda, which some years ago bought it from Heldref, a now-defunct educational foundation formerly based in Washington. Heldref had itself bought it in 1976—coincidentally, the year the Writer's Center was established—from its Boston owners. (The journal was founded by a pair of Shakespeare scholars in Philadelphia in 1889, but they soon moved themselves and it to Boston, where it lived until 1976.)

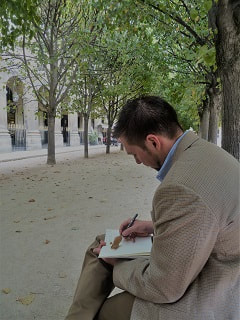

NB. Speaking of moving, Yours Truly, prosaic sole proprietor, editor, and contributor, apologizes for the last few weeks' hiatus: I had to move, only across town but somewhat unexpectedly, and it up all my time. NOTE: This is the first of a series of interviews with local writers. The emphasis in the interviews will be on the writing, editing, publishing, and marketing process, the behind-the-scenes, rather than on the books themselves. How do their works get from their minds to you? Our first writer is Derek Baxter, who's just found an agent for his first book. (Disclosure: Derek and I are both members of the critique group Arlington Creative Nonfiction Writers.) This interview was conducted by email in late September 2019-- and then again on 31 October 2019, when the author requested a correction. KOCH: Where are you from, where do you live, and what do you do for a living? BAXTER: Like Thomas Jefferson, the subject of my book—I’m an attorney from Virginia in his 40’s, roughly the same age when Jefferson explored Europe. The similarities only go so far, though—he accomplished more in a typical week than I do in a year. That’s one reason why I wanted to dig in and learn more about his life. How did you come to be a writer? I’ve taken classes on writing, read books on the subject, and gotten feedback from writing groups and peers. But the best way to become a writer is write: filling up page after page every day, then doing it again the next day, and the following. After a while, those words will show you what they have in common and that is your voice. You’re currently working on, correct me if I’m wrong, your first book: The Pursuit of Happiness: A Jeffersonian Roadtrip. According to your web site, it’s about your “experience following the route through Europe that Jefferson set out in Hints to Americans,” a route which begins in Holland and ends in France. When did you first begin work on it? And what motivated you to write this particular book? I’ve been working on the book for so many years that the title has had plenty of time to evolve. Now it decided to change its name to IN PURSUIT OF JEFFERSON: TRAVELING THROUGH EUROPE WITH THE MOST CONFOUNDING FOUNDER. In 1788, Jefferson compiled what he discovered from his own travels into a guide—intended for two wealthy young travelers—which he called Hints for Americans Traveling in Europe, setting out a detailed itinerary and subjects to explore. I decided to follow it and see what I could learn about Jefferson, the places I visited, and myself. I’ve spaced the big trips out, generally one per year, which gave me lots of time to research, plot, and write in between them. It’s given me something to do. On your web site you write: “Like Jefferson when he wrote [Hints], I’m 40-something, from Virginia, and searching for meaning in a life that’s stalled.” Can you talk a bit about this search and the role it played in developing your book? No better way than to unstall a life than to go on a quest. In the course of my journey following Jefferson’s travel advice, I boat on the same canals Jefferson did, make cheese in the same Italian town he visited, and walk around the same Roman ruins he measured. I learn how to consult the genius of the place when laying out a landscape, how to catch a codfish, and how to quarry marble. If you read the book you can experience some of these adventures too—and see if your view on Jefferson changes like mind has. You recently landed an agent, Amanda Jain of Bookends. Can you talk about how this came about? And did you consider self-publishing? I reached out to Amanda with a query letter and she responded. She has an interest in Tony Horwitz and Bill Bryson-style books, of travel with heavy dose of history mixed in. Now she’s helping send this book out into the world and I don’t know yet where it will go from here! I’ll let my book choose its own path. I only hope that it’s happy. With a fiction book you submit the manuscript, but with nonfiction you have to put together a book proposal. Can you talk about some of the challenges of putting a proposal together? I actually enjoyed putting the proposal together: it forced me to tighten up the structure of my book and throw some extra polish on my sample chapters. Doing market research on comparable titles taught me what ground my book will occupy. I revised the proposal dozens of times, with tons of input from writer friends. I spent the bulk of my time on it reworking my chapter summaries, again and again, honing just what will and won’t go into them and how they connect together. That was a worthwhile process worth in its own right. Writers today hear constantly about the importance of “platform.” What things do you do to build platform, and how do you feel about this aspect of the job? Ah, the platform. In my case jerry-rigged with duct tape. Creating your own brand isn’t easy for a first-time author, but I have a Facebook author site and write blog posts regularly for my website and sometimes for Monticello. Is there anything about living and working in the Washington, DC area that makes writing and marketing a book like this easier...or more difficult? When it comes time to market it, I’ll have to find some particularly DC way to do so, probably with a lot of free bite-size appetizers. Maybe I’ll fill the Jefferson Memorial for my book launch with a crowd of interns who are there for the food. The area does have everything I’ve needed and more: a great library system for research (and even the Library of Congress!), a thriving community of fellow writers to give advice, and a string of independent coffeeshops (the preferred habitat for my book while it grows up). And we’re within striking distance of Monticello, which I’ve traveled to dozens of times. Now, that inevitable question: Why should people read this book? My book invites you to join me on my travels. Through the pages of In Pursuit of Jefferson, you can vicariously experience some of the adventures I had: piloting a Dutch canal boat, tramping among French vineyards, making cheese in Italy, and hiking the Alps with Jefferson’s notes in my pocket. You can learn about subjects that intrigued Jefferson, like architecture and agriculture, and see how they’ve evolved since his day. On my trips, I got to know Jefferson better, seeing him as more human. And, of course, flawed. I deepened my understanding of how owning slaves, an unpardonable failure for this man who knew it was wrong, was crucial to his travels and lifestyle. If you read my book you can reach your own conclusions. But most of all, I hope that sharing the account of my journeys will inspire you to get out on the road yourself. His enthusiasm for travel, for putting himself out there and soaking in all the knowledge he could, is infectious. You, too, can follow pieces of Jefferson’s itinerary in Hints to Americans, or even just visit Monticello or Poplar Forest. Or make up your own route. And as you go, keep your eyes open for whatever you see on the road, just as Jefferson did all those years ago. What’s next for you after Pursuit? I have a few more book ideas up my sleeve, some more historical travel specials. But I can’t ruin the surprise! PHOTO CREDIT: Photo courtesy of Derek Baxter. |

AuthorI'm a freelance writer and editor who lives in Washington, D.C. Archives

March 2020

Categories |

© 2016-2019 Nathaniel Koch Email: [email protected]

RSS Feed

RSS Feed