|

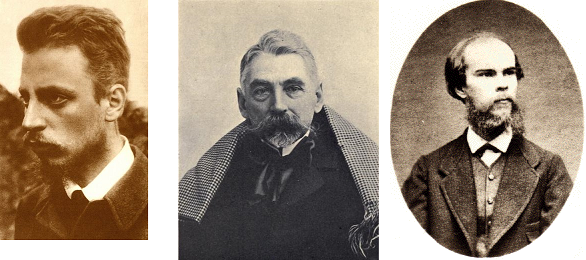

Washington may be a prosaic town, but it's also home to the "the nation's oldest poetry journal," as it calls itself. One hundred thirty years: that's how long Poet Lore has been in business. The biannual, which has published (among others) Rilke, Mallarmé, and Verlaine, is published by the Writer's Center of Bethesda, which some years ago bought it from Heldref, a now-defunct educational foundation formerly based in Washington. Heldref had itself bought it in 1976—coincidentally, the year the Writer's Center was established—from its Boston owners. (The journal was founded by a pair of Shakespeare scholars in Philadelphia in 1889, but they soon moved themselves and it to Boston, where it lived until 1976.)

NB. Speaking of moving, Yours Truly, prosaic sole proprietor, editor, and contributor, apologizes for the last few weeks' hiatus: I had to move, only across town but somewhat unexpectedly, and it up all my time.

0 Comments

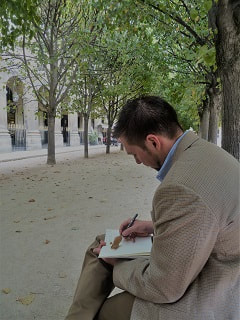

NOTE: This is the first of a series of interviews with local writers. The emphasis in the interviews will be on the writing, editing, publishing, and marketing process, the behind-the-scenes, rather than on the books themselves. How do their works get from their minds to you? Our first writer is Derek Baxter, who's just found an agent for his first book. (Disclosure: Derek and I are both members of the critique group Arlington Creative Nonfiction Writers.) This interview was conducted by email in late September 2019-- and then again on 31 October 2019, when the author requested a correction. KOCH: Where are you from, where do you live, and what do you do for a living? BAXTER: Like Thomas Jefferson, the subject of my book—I’m an attorney from Virginia in his 40’s, roughly the same age when Jefferson explored Europe. The similarities only go so far, though—he accomplished more in a typical week than I do in a year. That’s one reason why I wanted to dig in and learn more about his life. How did you come to be a writer? I’ve taken classes on writing, read books on the subject, and gotten feedback from writing groups and peers. But the best way to become a writer is write: filling up page after page every day, then doing it again the next day, and the following. After a while, those words will show you what they have in common and that is your voice. You’re currently working on, correct me if I’m wrong, your first book: The Pursuit of Happiness: A Jeffersonian Roadtrip. According to your web site, it’s about your “experience following the route through Europe that Jefferson set out in Hints to Americans,” a route which begins in Holland and ends in France. When did you first begin work on it? And what motivated you to write this particular book? I’ve been working on the book for so many years that the title has had plenty of time to evolve. Now it decided to change its name to IN PURSUIT OF JEFFERSON: TRAVELING THROUGH EUROPE WITH THE MOST CONFOUNDING FOUNDER. In 1788, Jefferson compiled what he discovered from his own travels into a guide—intended for two wealthy young travelers—which he called Hints for Americans Traveling in Europe, setting out a detailed itinerary and subjects to explore. I decided to follow it and see what I could learn about Jefferson, the places I visited, and myself. I’ve spaced the big trips out, generally one per year, which gave me lots of time to research, plot, and write in between them. It’s given me something to do. On your web site you write: “Like Jefferson when he wrote [Hints], I’m 40-something, from Virginia, and searching for meaning in a life that’s stalled.” Can you talk a bit about this search and the role it played in developing your book? No better way than to unstall a life than to go on a quest. In the course of my journey following Jefferson’s travel advice, I boat on the same canals Jefferson did, make cheese in the same Italian town he visited, and walk around the same Roman ruins he measured. I learn how to consult the genius of the place when laying out a landscape, how to catch a codfish, and how to quarry marble. If you read the book you can experience some of these adventures too—and see if your view on Jefferson changes like mind has. You recently landed an agent, Amanda Jain of Bookends. Can you talk about how this came about? And did you consider self-publishing? I reached out to Amanda with a query letter and she responded. She has an interest in Tony Horwitz and Bill Bryson-style books, of travel with heavy dose of history mixed in. Now she’s helping send this book out into the world and I don’t know yet where it will go from here! I’ll let my book choose its own path. I only hope that it’s happy. With a fiction book you submit the manuscript, but with nonfiction you have to put together a book proposal. Can you talk about some of the challenges of putting a proposal together? I actually enjoyed putting the proposal together: it forced me to tighten up the structure of my book and throw some extra polish on my sample chapters. Doing market research on comparable titles taught me what ground my book will occupy. I revised the proposal dozens of times, with tons of input from writer friends. I spent the bulk of my time on it reworking my chapter summaries, again and again, honing just what will and won’t go into them and how they connect together. That was a worthwhile process worth in its own right. Writers today hear constantly about the importance of “platform.” What things do you do to build platform, and how do you feel about this aspect of the job? Ah, the platform. In my case jerry-rigged with duct tape. Creating your own brand isn’t easy for a first-time author, but I have a Facebook author site and write blog posts regularly for my website and sometimes for Monticello. Is there anything about living and working in the Washington, DC area that makes writing and marketing a book like this easier...or more difficult? When it comes time to market it, I’ll have to find some particularly DC way to do so, probably with a lot of free bite-size appetizers. Maybe I’ll fill the Jefferson Memorial for my book launch with a crowd of interns who are there for the food. The area does have everything I’ve needed and more: a great library system for research (and even the Library of Congress!), a thriving community of fellow writers to give advice, and a string of independent coffeeshops (the preferred habitat for my book while it grows up). And we’re within striking distance of Monticello, which I’ve traveled to dozens of times. Now, that inevitable question: Why should people read this book? My book invites you to join me on my travels. Through the pages of In Pursuit of Jefferson, you can vicariously experience some of the adventures I had: piloting a Dutch canal boat, tramping among French vineyards, making cheese in Italy, and hiking the Alps with Jefferson’s notes in my pocket. You can learn about subjects that intrigued Jefferson, like architecture and agriculture, and see how they’ve evolved since his day. On my trips, I got to know Jefferson better, seeing him as more human. And, of course, flawed. I deepened my understanding of how owning slaves, an unpardonable failure for this man who knew it was wrong, was crucial to his travels and lifestyle. If you read my book you can reach your own conclusions. But most of all, I hope that sharing the account of my journeys will inspire you to get out on the road yourself. His enthusiasm for travel, for putting himself out there and soaking in all the knowledge he could, is infectious. You, too, can follow pieces of Jefferson’s itinerary in Hints to Americans, or even just visit Monticello or Poplar Forest. Or make up your own route. And as you go, keep your eyes open for whatever you see on the road, just as Jefferson did all those years ago. What’s next for you after Pursuit? I have a few more book ideas up my sleeve, some more historical travel specials. But I can’t ruin the surprise! PHOTO CREDIT: Photo courtesy of Derek Baxter. You know the story. A divorced mom moves from L.A. to D.C. to star in a movie that’s being shot at Georgetown University. When her 12-year daughter conjures up an unhealthful imaginary friend with a Ouija Board, weird stuff starts to go down—driving mom to seek the help of a buffed-out psychiatrist-priest, who’s also new in town and who’s got baggage of his own... It’s essentially a kidnapping story, one in which the mysterious kidnappers send the mom a string of torture-videos through the girl herself. The rogue cop of a psychiatrist-priest, Damien, having agreed help the mom, goes to the Department to get permission to go in after the captors. The higher-ups agree. On one condition: that a nutty old hand, who’s on a mission of his own, it's personal, lead the operation. Showdown ensues. There’s also a pair of red herrings in the form of a Teutonic butler and maid, and a murder subplot involving a detective who seems to be running the Metropolitan Police Department by himself. Though it helps to break up the main story, which is set almost entirely in the heroine’s rented Prospect Street house, the subplot keeps getting in the way. The detective wanders around too much. He ruminates aloud a bit too much; he pores over evidence for a bit too long. The trouble is that we know that none of this sleuthing is going to matter at all to the resolution. After all, if God’s Own Commandos—and that’s how the book presents its Jesuits—can’t fix this then what's the D.C. Government going to do? Even in the 2011 revision, in which he polished his one-draft original, Blatty overwrites some of the dialogue, laying in every huh? and what? By way of getting across the movie-making and medical and theological details, in which much of the book's interest lies, he has his characters explain them to one other, like so many Sherlocks to Watson. (The Watson role usually falls to the mom, Chris, who unfortunately for the reader is shallow and an irritant: under her career and wealth she’s just another bird-brained damsel who needs a man to rescue her.) There are an awful lot of significant stares and narrowed eyes and wide eyes and rolled eyes and gazes cast askance. There’s no shortage of hokum, too, a fair amount of it tasty—and outside the rectory with its humorous priests, a lot of cliché (the loner detective, the chilly ex-husband, the binge-drinking Brit). And although the serpent may be the subtlest of beasts, subtle this book ain’t: every foreboding has bells on and every dropped clue makes a reverberating ka-boom! (The 1973 FX movie, adapted by Blatty himself, faithfully preserves the book's garish, noisy, high-strung style, although it leaves out most of the talky exposition and cuts early to the bedroom chase.) What this book does brilliantly is plotting and pacing. The story leaps out of the gate of a brief adventure-movie prologue in Iraq and seldom drags after that. Blatty clearly made good use of what he brought to and learned in Hollywood, where story is everything and the shark fin must get on screen within the first twenty minutes. The parts are carefully arranged, nothing is overlong, and every other chapter ends with a cliffhanger—like cut to the chase, a loanword from the movie world. That the novel works as well as it does is a testament to Blatty’s skills, because as Damien himself points out, possession makes no sense. Why would an invisible super monster let us know it’s there and what it’s doing, like some crappy Bond Movie Villain? Even merely human crooks—think Harold Shipman or Robert Hanssen—know how to hide their M.O. and their footprints. Because The Exorcist and its sequels and adaptations went on to overshadow the rest of his output, it’s easy to forget that Blatty was already a veteran at the time he started working on the manuscript in 1968. By then he had two books and eight screenplays to his credit—mostly comedies. It’s tempting, too, to finger the cultural climate for the book’s success: even more than most, the early 1970s were a time when it must have seemed to almost everyone that foulness was afoot and our experts were in over their heads. In fact, the novel was floundering until, as he told it later, Blatty was invited onto what turned into a 40-minute sales pitch on The Dick Cavett Show*. The book went straight from the TV appearance to the top of the New York Times fiction bestseller list, where it remained for four months. The period’s other #1 bestsellers were neither especially horrific nor especially demonological. Blatty, who spent his final years in Bethesda, said he was inspired by a story of an alleged case of possession he heard about in 1949, when he was a scholarship student at Georgetown—a story that had found its way into The Washington Post and was making noise around campus. (In the late 1990s local writer Mark Opsasnick wrote what is, as far as I know, still the definitive account of that original story and of what didn’t happen in 1949.) A number of elements from the ’49 case, like the “levitations” and the words appearing on the victim’s skin, appear in The Exorcist. Blatty changed the boy into a girl, moved her from Prince George’s County to Georgetown, and upgraded the mom to a movie star. In all this he was just writing what he knew—and the moviemaking details are among the most interesting in the book. (The book’s one Washington Party Scene isn’t as convincing.) But…that movie. A jillion Lucasfilms later, the 1973 adaptation, with a fourteen-year-old Linda Blair got up in Caligari greasepaint, remains one of the top-grossing movies of all time. It’s also a culturally significant artifact, according to the Library of Congress, which (in 2010) put it on the National Film Registry. Our preservationists may not know how right they are...and not just because of the occasionally literal hysterics and heart attacks spawned by the movie, which got mixed reviews in 1973. According to Fordham prof Michael Cuneo’s 2001 investigation of Charismatic-Revival Christianity, American Exorcism—a look into the televised exorcisms, Satanic Panics, and mass deliverances of the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s—it was all down, or a lot of it anyway, to that movie. To life imitating art, far beyond the appearance in the early 1970s on the real Georgetown exteriors of a real movie crew with a real movie star (Ellen Burstyn) playing the book’s made-up movie star. Are authors to blame for what people do with their work? Does the stuff in this book really exist? Here’s one thing everyone can agree on: a dazzling yet mysterious power stalks the world, a power that can persuade us that lies are true. The creature hath a name: motion pictures. Cut! Print the myth! *Cavett’s other guest had to leave early. His name? Robert Shaw, who would go on to play Quint in the horror comedy flick Jaws (1975)…the way for which would be paved by The Exorcist. PHOTO CREDIT: Public Domain. Goya, St. Francis Borgia Helping a Dying Impenitent, 1788. A: 1949 in Cottage City, Maryland, which is just across the District line in Prince George's. For an investigation of the story at the base of the novel, see local writer Mark Opsasnick's excellent longform piece in Strange Magazine #20 (1999). (Issue #20 was the magazine's last in print; the magazine continues in an online edition.) In this month's Capsule: The Exorcist (1971). Where and when was the actual "exorcism" case that William Blatty adapted into his Georgetown-set bestselling novel, The Exorcist (1971)?

PHOTO CREDIT: Lenka Reznicek, 2006. Reduced. Licensed under CC BY 2.5. This detective’s-eye view of Washington, written by a former MPD (Metropolitan Police Department) officer, begins in the dead of winter. Detective Ezra Simeon, who does the narrating, has just been “detailed” (or relegated) to work in cold cases, having just contracted a case of stroke-like Bell’s Palsy. After being shifted again to homicide, he picks up a murder case involving some unlikely suspects and victims—a case which, in some of its details, closely resembles one of the cold murder cases he’s already worked on. As he gets nearer to the bottom of it, things take a startling, though not implausible, turn. On the way there we follow Ezra through the day-to-day of police work: the office politics and paperwork, the subway accidents and subpoenas and DNA tests, the cold calls and interviews, and the endless driving (sometimes with a partner) from station to diner to Judiciary Square to crime scene and back again. As a camera, Ezra works beautifully. The workmanlike writing and laconic style convey authenticity; so does Ezra’s perpetual, carefully detailed fatigue. But when we’re alone with him and his thoughts in his cruiser or his Chinatown mouse-hole—and Swinson spends a lot of ink characterizing him—there often doesn’t seem to be quite enough there. We know his father was a Secret Service agent and that he (Ezra) grew up in D.C. We know he’s divorced, and that back in California, through his ex, he’d been mixed up with the punk music scene. (The author’s own bio is similar.) Apart from whisky and cigars, his sole hobby—and the detectives are depicted as living their work—seems to be chatting and meeting with his L.A. friend, Clem. There’s a lot of transcript-like dialogue and interrogation, too, which gets across Ezra’s shrewdness, but he himself never fully comes across. And there’s perhaps too much elaborated-on slapping of alarm clocks, sipping of coffee, fighting of traffic, and logging into computers: the tedium of the job could have been got across in some more efficient way. Many readers will surely seek out this book, Swinson's first novel, which feels at times like a policeman’s diary, for its documentary aspects. Here it satisfies, with (among other things) up-close pictures of places like just-gentrifying Columbia Heights, Chinatown, and upper New York Avenue. There are few chronological cues—no TV shows, no movies, no period radio stations playing period Top 40. There’s an Xbox, though, and HDTV, and Adams Morgan (annoyingly Adam’s Morgan, every single time, in my Dymaxicon softcover) is already gentrified. All this puts the setting no later than the early 2000s, though, with those few cues, the story often feels as if it could be taking place at any point since 1991, the local end of the peak of the Great American Crime Wave, which was just starting to wane in the early 2000s. As people here never tire of saying, Washington (like most American cities) has changed a lot in twenty years. Along with giving us a readable story that only rarely bogs down, A Detailed Man captures that time when the Cool “Disco” Dan days had still not quite given way to Forbes Magazine’s redeveloped Cool D.C. PHOTO CREDIT: Tony Webster, 2018. Reduced. Licensed by CC BY 2.0. Last week we looked at the military population of the metro area. This time we'll look at some of the locally produced military publications:

First, there are the official products of Defense Media Activity (DMA), based at Fort Meade, MD. These include Airman, All Hands, defense.gov, army.mil, navy.mil, af.mil, and marines.mil. The best known is the editorially independent Stars and Stripes, with four overseas print dailies plus a domestic weekly; the successor of a Civil-War-era journal, it is produced at the National Press Building. The DC area's military academies and universities have their own publications: Prism and Joint Force Quarterly out of National Defense University at Fort McNair in Southwest; MCU Journal (Marine Corps University, Quantico); Defense Acquisition Magazine (Defense Acquisition University, Fort Belvoir, VA); Journal of Strategic Intelligence (National Intelligence University, Bethesda). The U S Naval Academy publishes Shipmate for alumni, and its midshipmen publish a “humorous periodical,” The Log. Then there are the journals, sometimes more than one, of the professional associations--of the US Naval Institute in Annapolis, the Marine Corps Association (Quantico), the Air Force Association (Arlington), the Association of the US Army (Arlington), and the Military Officers Association of America (Alexandria). The Army & Navy Club publishes The Dispatch. There’s also The Defense Monitor, published by the Project on Government Oversight (POGO). There are the several editions (Army, Navy, Air Force, Marine Corps) of Military Times, published by Sightline Media in the Virginia suburbs; Sightline also publishes Defense News and C4ISRNET. Finally, there are a host of locally produced commercial magazines devoted to military topics, like America’s Civil War Magazine (Leesburg), Small Wars Journal (Bethesda), and Vietnam Magazine (Vienna). Though this survey isn't complete, it hints at the scale of this local publishing sector, a lot of which accepts work from freelancers. Which American cities have the most writers? On the way to returning to tackling the question of how many writers there are in the DMV, let's first look at the same government data (the Occupational Employment Statistics) for some other cities (the cited tables, below, can be found about half way down the Bureau's page): 27-3043 Writers and Authors: Rank Metro area -- Employment (Employment per thousand jobs) 1 New York-Newark-Jersey City, NY-NJ-PA -- 7,490 (0.79) 2 Los Angeles-Long Beach-Anaheim, CA -- 4,680 (0.76) 3 Washington-Arlington-Alexandria... -- 2,230 (0.71) 4 Chicago-Naperville-Elgin, IL-IN-WI -- 1,770 (0.38) 5 Boston-Cambridge-Nashua, MA-NH -- 1,320 (0.48) 27-3022 Reporters and Correspondents: Rank Metro area -- Employment (Employment per thousand jobs) 1 New York-Newark-Jersey City, NY-NJ-PA -- 4,400 (0.46) 2 Washington-Arlington-Alexandria, DC... -- 2,120 (0.68) 3 Los Angeles-Long Beach-Anaheim, CA -- 1,460 (0.24) 4 Chicago-Naperville-Elgin, IL-IN-WI -- 850 (0.18) 5 San Francisco-Oakland-Hayward, CA -- 840 (0.35) 27-3042 Technical Writers: Rank Metro area -- Employment (Employment per thousand jobs) 1 Washington-Arlington-Alexandria, DC... -- 3,590 (1.15) 2 New York-Newark-Jersey City, NY-NJ-PA -- 3,230 (0.34) 3 Boston-Cambridge-Nashua, MA-NH -- 2,200 (0.80) 4 Dallas-Fort Worth-Arlington, TX -- 1,850 (0.52) 5 Los Angeles-Long Beach-Anaheim, CA -- 1,630 (0.27) It will surprise no one that, according to these data at any rate, the most professionally writery American cities are New York, Los Angeles, and Washington. (These OES data count only salaried professionals; they exclude the self-employed and the moonlighter.) The capital is a relatively good place to work as a salaried technical or professional writer. How a good a place is to be a struggling or not struggling novelist or a short-story writer or poet or a writer of commercial nonfiction? Does where you work on such things even matter, and if so, why? And supposing that Washington's a bad place to work on them, as some people say, why is that? To be continued... "The Snow Storm," writes Kim Roberts in her book A Literary Guide to Washington, DC (2018, Univ. of Virginia Press), "was DC's first race riot. It was begun in August 1835 with an alleged nighttime attack by Arthur Bowen, a nineteen-year-old slave, upon his owner, Anna Maria Thornton, aged sixty, widow of the architect of the Capitol, William Thornton."

Bowen was imprisoned. A mob of mostly Irish immigrant laborers tried to storm the jail, located on the site of present-day Judiciary Square, in order to hang him. The Mayor, District Marshal, and U S District Attorney (as U S Attorneys were then called) worked to pacify the mob; when their efforts failed, Marines were sent to guard the jail. The mob then went off and burned or damaged a number of churches, schools, homes, and businesses run by or for blacks-- including a restaurant run by a certain Mr. Snow (thus the "Snow Storm"). Here's a contemporary diarist's account of the events: "The 7 of August 1835 on friday it was reported that Mrs Doctor Thornton young Mulatto man said that he was going to knock his mistress in the head with axe and he were arrested and put in the Jail still the mob raged with great vigor and as fast as they were arrested they were lodged in Jail on the 8 day of August 1835 on saturday the mob surrounded the Jail and swear they would pull the Jail down and the Constable makin threats they said their objects was to get Mrs Thortons Mullateto man out and to hang him with out Judge or juror and evry effort was made by the Marshal of the District and the united States District Artoneny lawer Frances key Sr and the Hon Wiliam A Bradly that wher Mayo[r] of washington at that time evry efert wher made by the oficers to preserve peace and harmony among these men but all of it appeard in vain and they wher not surfichient Milertary force to guard the Jail..." The Attorney? Francis Scott Key, author of the words to "The Star-Spangled Banner." The diarist? Michael G. Shiner, a former slave, freed in 1836, who worked at the Navy Yard. Read his memoir-slash-diary, "the earliest known by a DC resident of African descent," according to Ms. Roberts. America, as you might expect, publishes a large number of military newspapers and magazines. Many of them are produced in Washington; next week we’ll take a look at them.

First, though, let’s look at the local military presence. Everyone knows about the Pentagon, but because uniforms and tanks and bombers are relatively scarce here, civilian residents and visitors don’t always think of the capital as a military town. In terms of the number of military people, though, it ranks third in the country, right after the gigantic navy centers in San Diego and at the mouth of the James: Rank - Metro area / Military population (thousands)* 1 - San Diego, incl. Camp Pendleton 206 2 - Hampton Roads** 186 3 - Washington 147*** 4 - Fort Bragg 112 5 - Honolulu 106 *”includes active duty personnel, families, and members of the military base or installation” **Chesapeake, Hampton, Newport News, Norfolk, & Virginia Beach ***Includes Arlington, Fort Belvoir (VA), and Fort Meade (MD) Nearby Baltimore, Philadelphia, and Richmond? None are in the top 100. Indeed, no American city of comparable size has anywhere near Washington’s military population. It’s true that the concentration in the capital is much lower than it is in, say, Hampton Roads or Honolulu—where one out of every ten residents is a Pentagon employee or a spouse or dependent or base worker. Still, the military leaves a mark on the DC region and its culture in many ways—not least in writing and publishing, as we’ll see next week. |

AuthorI'm a freelance writer and editor who lives in Washington, D.C. Archives

March 2020

Categories |

© 2016-2019 Nathaniel Koch Email: [email protected]

RSS Feed

RSS Feed